Minimalism is due for a reckoning

We are approaching a turning point for the politics and aesthetics of modern brands

Walk around SoHo or browse through the ads you see on Instagram and you’ll notice it. There is by now a very well defined, regimented aesthetic for how cool young brands should look. While there isn’t some cookie cutter template for how millennials dress, there is very much a template for brand and product design. Think Away, Glossier, Curology, Harry’s, Article, and Outdoor Voices. Clean lines. Muted tones. Sans serif fonts. A Japanese/Scandinavian-inspired minimalist sensibility that carries over beyond visual design and into tone of voice and feel.

This is the culmination of a few different things. Smartphones and mobile ecommerce meant that brand and product designers needed to build for smaller screens, which means simpler logos, clearer fonts, and design schemes that translate easily between desktop and mobile browsers. Airbnb famously underwent a significant rebranding to better accommodate mobile users. (TechCrunch) The rise of direct to consumer commerce (DTC) has led to smaller companies that needed to be more focused and carry smaller selections to move quickly. The entire consumer ecosystem has become perfectly calibrated for these type of brands to deliver those types of experiences.

Call it DNVB (digitally native vertical brands), DTC, or modern luxury, but there is clearly a common denominator. Lean Luxe founder Paul Munford even went so far as a to spell out the template for what makes “Modern Luxury” brand (Lean Luxe). TL;DR: Things that are cool today are cool because they appear naturally-imbued with style, not because they have swagger. Brands strive to exude the same kind of “quiet confidence,” to project ease above all.

But now I’ve begun feeling that we’re hitting a saturation point with “luxury minimalist” brands. Everything looks great but it also all looks the same. This kind of aesthetic has become the fastest shortcut to legitimacy for new brands. It’s also become very goddamn boring. And maybe irrelevant. From the Ringer:

Earlier this year, I was astonished—maybe more than I should have been—to hear a 17-year-old I know use the word “millennial” to mean someone significantly older than she is. Because this particular 17-year-old is incredibly wise, I asked her to describe what she thinks of when she thinks of the word “millennial.” After the requisite jokes about avocados and chain restaurants, she considered the question more deeply. “Maybe this is stupid,” she said, “but the first thing that comes to mind is, like … Glossier. That whole clean, minimalist advertising aesthetic. People wanting to make life less messy, and make life ‘easier’ … but only really for their generation and people like them.”

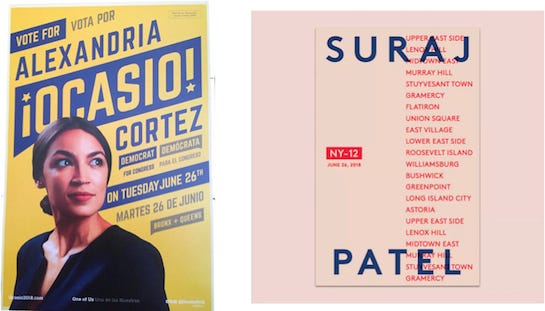

All the brands built for millennials were built in response to something. Eventually, the pendulum will have to swing back over. I’m thinking 80s-inflected maximalism for new brands. Loud. Brash. Bric a brac. The signs are there if you know where to look. The rise of ugly, oversized sneakers, for instance, might herald a changing of the guard. (The Cut) Fashion is a leading indicator, even if it moves in more extreme ways than mainstream consumer. But speaking of the mainstream consumer, Ikea seems to be catching on as well:

Millennials came of age in the crucible of the Great Recession and so crave the comforts of access and ease to soothe the anxiety of knowing we’re fucked. Millennials are liberal, but not radical. Millennials feel the pain of the opportunity and future that was taken away from us because the olds pissed our economy away. The next generation seems roaring to build. And, cynically, the people who want to build the next wave of great brands for them will have to internalize and cater to that aesthetic and those politics.

DNVBs are dead. Long live DNVBs.