I know it’s been a very long time. Whenever I stop writing I start feeling like I can’t start again until I have something really good, which… 1) nothing I write I ever really good and 2) is bullshit. But still, that 100% endogenous pressure just compounds over time even as the writing habit/muscle atrophies and picking it up again becomes harder.

The point is, I’m back with my usual bullshit/garbage. Enjoy, my fellow trash monsters.

Buy: this sick burn of Carlyle x Supreme parody tee from Hasan Minhaj. Or don’t because it’s totally sold out and reselling at 10x markups. (Patriot Act Store)

Watch: Bodyguard on Netflix. Shades of House of Cards but way more British and slightly less dumb. Tbh I still don’t super get all the twists but it’s a fun watch. (Trailer)

Also make sure to check out the long block at the bottom where, in light of news about China’s social credit system, I’ve republished a post on surveillance and credit-worthiness from the old 99D.

Enjoy.

The death of small businesses in big cities, explained - Rebecca Jennings, The Goods

Couple of things I liked from this interview about neoliberalism and local businesses. One thing in particular stood out in a larger point about developers creating pop-up locations:

They’re curated by these developers, but there’s nothing organic. There’s nothing truly urban or diverse about them. You can’t start a business with a one-year lease. In the first year, you don’t make any profit. If we are a society, we need each other, and we need those small-business people to maintain the social network of our neighborhoods, and they’re being destroyed. Pop-ups are not going to replace that.

It’s interesting to think about how pop-ups don't represent urban dynamism/chaos/vitality but instead are inorganic representations of it - that they’re most like facsimiles of city life. Reminds of this great essay from Amanda Hess in the New York Times: The Existential Void of the Pop-Up ‘Experience’.

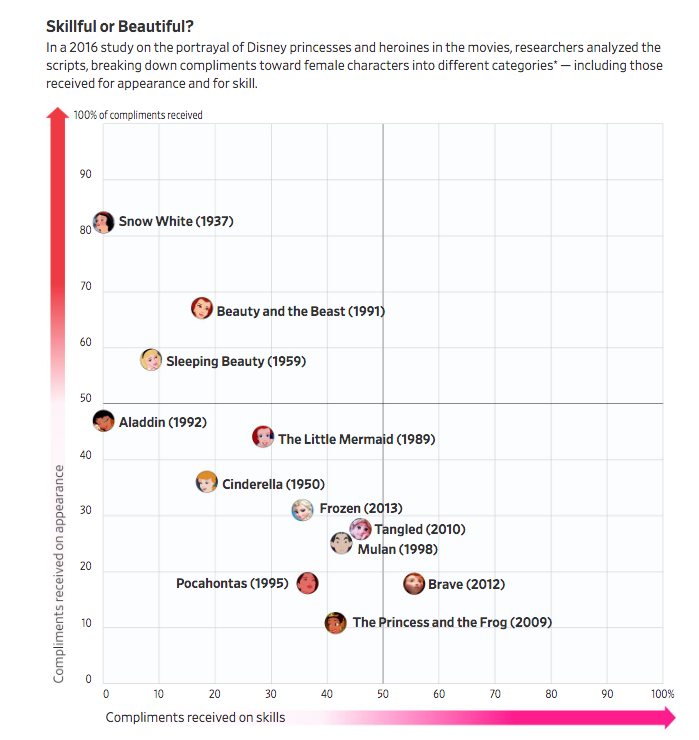

Beauty and the Backlash: Disney’s Modern Princess Problem - Erich Schwartzel, WSJ (paywall removed)

For nearly 20 years, Disney employees have debated how far the company should go in updating its heroines for the modern age. The crux: How do you keep princesses relevant without alienating fans who hold fast to the versions they grew up with? Billions of dollars of revenue—dolls, sequels, stage shows and dresses—hang on getting that balance right.

[…]

Disney develops and manages characters such as Mulan or Rapunzel similar to the way Apple Inc. handles new iPhone models, with a secretive process that allows the princesses to debut in public fully formed. Interviews with nearly two dozen current and former employees working across Disney’s sprawling princess operations reveal a perennial push-and-pull over getting the mix of tradition and modernity right, from producing remakes and merchandise built around longtime characters to introducing new characters.

David Stern has no time for war stories - Chris Ballard, Sports Illustrated

The Commish has not slowed down since stepping down from the NBA.

To spend time with Stern is to note his brash, tell-it-like-it-is charm, but to also feel as if he's about to hand out an exam, only you're not sure what it's on. His default expression communicates that he is listening to you just long enough to form an opinion or to marshal an argument. He has a tendency to make pronouncements that are directly confrontational but, upon further review, also true.

I’m a sucker for a good profile, sue me.

You Already Email Like a Robot — Why Not Automate It? - John Hermann, New York Times Magazine

Fair point. Email-talk is weird. Great read on what Google’s quest to automate our email writing reveals about the mode of communication itself and our modern working world.

If, for example, it suggests a certain completion, and enough users take it, that one will be more likely to appear in the future. If a canned reply is never used, this is a signal that it should be purged; if it is frequently used, it will show up more often. This could, in theory, create feedback loops: common phrases becoming more common as they’re offered back to users, winning a sort of election for the best way to say “O.K.” with polite verbosity, and even training users, A.I.-like, to use them elsewhere. Such a dynamic would take root only where a behavior is already substantially automated — typed, at work, more as a learned performance rather than as an expression of will, or even an idea. Smart Compose is, in other words, good at isolating the ways we’ve already been programmed — by work, by social convention, by communication tools — and taking them off our hands.

One particularly great detail here is that the basis for the machine learning models Google uses for Smart Reply and Smart Compose is a cache of 600,000 emails from Enron made public through discovery, now know as “The Enron Corpus.” It’s apparently the biggest such set of emails out there. For more, check out this read from 2013:

The Immortal Life of the Enron E-mails - Jessica Leber, MIT Technology Review

Beijing to Judge Every Resident Based on Behavior by End of 2020 - Bloomberg News

China’s plan to judge each of its 1.3 billion people based on their social behavior is moving a step closer to reality, with Beijing set to adopt a lifelong points program by 2021 that assigns personalized ratings for each resident.

The capital city will pool data from several departments to reward and punish some 22 million citizens based on their actions and reputations by the end of 2020, according to a plan posted on the Beijing municipal government’s website on Monday. Those with better so-called social credit will get “green channel” benefits while those who violate laws will find life more difficult.

Been talking about this one for a while so I want to re-up a post from the old 99D about this (in full below):

Surveillance and Credit - January 3, 2018

I got into an argument with a lady on a plane. A flight attendant had to be called. The details of this fight are not important but to suffice to say the stewardess wound up apologizing to me and various passengers remarked to me that the lady was crazy. So I was right and I won. I was even given an opportunity to file a complaint against my new nemesis!

Filing the complaint would have had one of two possible outcomes: either nothing would happen because the complaint would go into a void where it wouldn’t merit enough attention to demand followup, or it would linked to the lady’s customer data in the airline’s customer relationship management database. In the former case, it would obviously not matter. In the latter case, the complaint could follow my enemy around like a scarlet letter, marring any and all future interactions with customer service reps from the airline who, upon opening her file each time she called, would see a note about her being “difficult” on a flight in late 2017. That might make them less likely to do her favors in the future. Each denied request would be my small victory.

I did not wind up filing the complaint against her for two reasons: the first was the it seemed like too much bother. My pettiness and vindictiveness are only matched by my laziness. The other reason was my fear that filing a complaint could go on myrecord in the airline’s CRM (they software they use to keep customer records). So, as is often the case in my petty feuds, nothing happened.

We are increasingly at the mercy of invisible, un-questionable data and analytical systems that drive crucial life events like who we meet, what job we can get, whether we can buy a house, etc. So an online tiff might seem silly and frivolous until it potentially affects your ability to book a flight. This is explored really well in the January 2018 issue of Wired, which delved into the depths of China’s “Social Credit Ratings,” and Alibaba’s “Zhima Credit” score, each more technologically and ubiquitous versions of credit scores:

Like any conventional credit scoring system, Zhima Credit monitors my spending history and whether I have repaid my loans. But elsewhere the algorithm veers into voodoo, or worse. A category called Connections considers the credit of my contacts in Alipay’s social network. Characteristics takes into consideration what kind of car I drive, where I work, and where I went to school. A category called Behavior, meanwhile, scrutinizes the nuances of my consumer life, zeroing in on actions that purportedly correlate with good credit.

This is fairly insidious in China as it is also an authoritarian tool to enforce compliance and punish deviancy. Critiquing the government online by “spreading false rumors” warrants a cut to your score under this system. Associating with a low score (deviant) person, brings down your score, thereby isolating the malcontents.

In a country with low rates of bank adoption, poor credit histories, and high rates of fraud, there was a need for an alternative system of verifying trust and creditworthiness. This “Social credit” system, whereby your credit score is determined through alternative means like spending history, is not an overall bad idea. It’s a good way of taking previous ideas about creditworthiness (social capital) and applying them to a financial system. It can work well. I know this because this is how our modern credit system started in the west: with chivalric credit.

In late medieval Europe, creditworthiness was a simple matter of exhibited social merit. Historian Martha Howell writes, “To give, not just to receive, a gift was to earn honor. The language of honor had long surrounded gift-giving in Europe, for gifts were an essential feature of the medieval aristocracy’s culture of honor, but in this new age honor had new work to do, and it had acquired new importance throughout society.” This was the most significant supra-market value of gifts: their ability to transmit information not just between giver and receiver but also to the rest of society. Gifts to charity and other lords were recorded in public ledgers, which stood as a testament and record of one’s standing. (This is all well and good for lords but functionally prevented the plebs from accessing credit). It mostly kind of worked.

So today, given a rapidly growing banking system where traditional credit scoring/histories can’t keep up with the adoption of financial technology, a system of the same nature might make sense. There are real dangers, however, even beyond China’s authoritarian impulses. There’s the danger of codifying prejudice; letting the new analytical frameworks work off of the old, discriminatory ones. I covered this in “Equality is Fucked”:

by analyzing large data sets, police departments can preemptively deploy patrons to high crime areas. This increases the perception of police presence and perception of risk, thereby lowering crime. Thing is, just like ads for jobs or homes created feedback loops by serving them to people based on race, predictive policing creates feedback loops by deploying officers to monitor neighborhoods with historically high crime rates […] without consideration for the fact that is is built on a legacy of racism and surveillance.

Basically, the application of “big data” to credit scoring could wind up just looking a lot like digital red-lining. On a deeper level, this also introduces an explicit surveillance component to our financial system. When every purchase, every trip, every bad habit is monitored to determine credit worthiness, each of those moments will become as stressful as filling out a loan application, or at least as un-free. Knowing we’re being watched affects how we behave.

It’s important here to note how sea change in surveillance obviates our previous mental model for surveillance: the Panopticon. Rather than being placed in a prison under invasive watch, we’ve let the guards into our houses and handed over our data, not just willingly but happily. This is what Bernard Harcourt calls the expository model of surveillance. The biggest companies on the planet make their money in one way or another by knowing our habits intimately, knowledge we hand over happily. We’ve exposed ourselves, giving greater access than the Panoptic model ever could wrench from us.

There’s a final, harsh edge to all this: the black box of big data and secret scores. We don’t know the inner workings of these systems and we certainly can’t challenge them. Perhaps the most anodyne version of these data systems (social media) at least maintains a charade of transparency. We know that data is collected, even if we don’t have control over how our data is used for (or against us).

Facebook ads are an easy to comprehend if an imperfect example. Facebook allows advertisers to create sponsored posts (so called “dark posts”) that are only visible to the targeted audience. You can’t find them anywhere unless you are part of the target for the ad. This means that if, for instance, an employer is advertising job postings to a certain age demographic, the ad is invisible to anyone outside that age group. Mind you, this is illegal age discrimination. But you can’t prove a negative so you’d never know which ads (job postings, housing, etc.) you’re not seeing. Facebook is currently being sued over exactly this.

Because these systems are invisible, they can’t be reasoned with or appealed to. If we don’t know why our social credit score is being dragged down, we can’t fight it. If, for instance, your old Tumblr account got hacked and started posting spammy content, that could make you seem like a spammer and so seem less trustworthy, lowering your credit and making it harder to buy a house.

It is essential that we modernize credit and lending systems. Today, you need debt to get debt and an unpaid bill from a decade ago can kneecap a job application. But the example of China’s Social Credit system shows the inherently surveillant quality of credit monitoring. Government has to step in and create new guidelines for modern lending and reform existing credit reporting/scoring practices. But it will take a thoughtful approach that pays attention to just how wrong this can go.

In the US, we have have systems in place to stop abuses of power. Those systems will only work if we have the ambition and determination to use them.